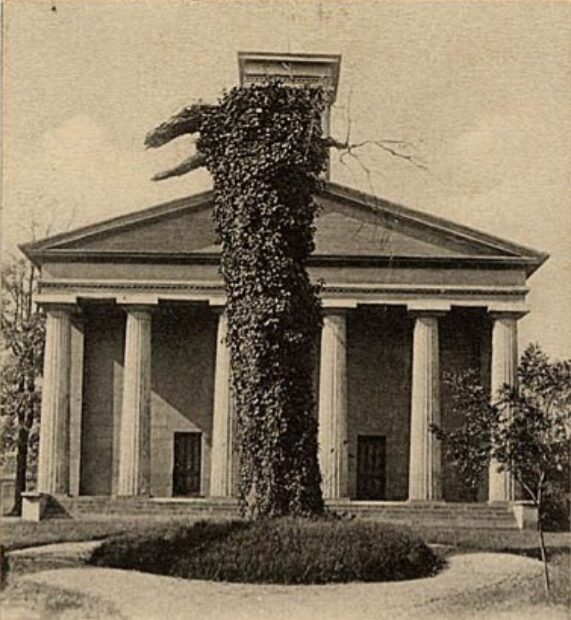

The remains of the Toombs Oak in front of the University of Georgia’s historic chapel.

By Steve Armour, University Archivist, University of Georgia

Contributing to the Locating Slavery’s Legacies database (LSLdb) was a rewarding experience in the fall of 2023. As the University Archivist at a large, old, southern institution like the University of Georgia (UGA), I am greatly invested in the work of adding depth and context to our understanding of campus history. LSLdb is a key resource for highlighting the areas where UGA aligns and differs with other institutions in regard to monuments, memorials, building names, and the messages we send with these features of the built environment. The database is particularly suited to unearthing these aspects of the campus, both within and across colleges and universities.

In this post, I seek to highlight a single monument that has had more than one iteration, which made for an interesting experience of recording it in LSLdb and for thinking about the ways monuments change over time. That monument is the Toombs Oak, which was once a living tree, but its legend and its landmark status have long outlived the tree. This majestic oak once stood on the front lawn of the campus chapel, and was named for Robert Toombs.

Toombs was a lawyer, enslaver, and statesman who served in the Georgia legislature and both houses of Congress before assuming the position of Secretary of State of the Confederacy, and later served as a brigadier general in the C.S.A. Before his storied Confederate career, he was a University of Georgia student who ran afoul of President Moses Waddel and got himself expelled for his habits of drinking, swearing, and fighting. Toombs would appeal his expulsion and be reinstated, only to be permanently expelled in 1828.

Not one to go quietly, Toombs was said to have appeared at the following commencement ceremony where he gave a speech so stirring from beneath an oak tree that the entire audience poured out of the campus chapel to hear him. According to legend, the tree was struck by lightning at the very moment of Toombs’ death in 1885 and never recovered. Indeed, many photos of the oak depict what can only be described as a rather tall and ugly stump. After years of slow decay, the remaining “tree” fully collapsed in 1908 and the remnants were cut into mementos that have been passed down by alumni. The University Archives has a gavel carved from the wood of the Toombs Oak. To commemorate the tree, the class of 1908 commissioned and installed a sundial in its former location. The sundial was stolen from its pedestal in 1971 (no one has ever confessed or been caught), but it was replaced in 2008 and a dedication ceremony was held for the occasion. In 1987, a state historical marker was erected near the site to explain the history and legend.

Toombs’ legacy on campus has been honored through a number of different memorials—a tree, mementos carved from the tree, two different sundials, and a historical marker—but such fanfare begs the question of what exactly is being held in such high regard. Toombs was a hellion at the University of Georgia who reportedly assaulted his classmates with a bowl, a club, a pistol, or anything he could get his hands on. He disrupted commencement, a sacred rite of passage for his UGA peers and a major public event in the state, to attract attention to himself with a fiery speech. Was the speech Toombs’ attempt to make a compelling case that his ejection from the University had been unwarranted? That sounds like a tall order, but unfortunately there’s not a shred of evidence or hint of a rumor regarding what Toombs might have said in this supposedly gripping oration before hundreds of enraptured listeners. Another interesting feature of the Toombs legend is the claim that the University offered him a degree years later, after he had achieved political fame, and that Toombs rejected it on the grounds that he would be unjustly conferring honor to UGA by accepting it now, when he had been denied such honor as a student. Historian E. Merton Coulter points out that the whole legend fails to take into consideration that Toombs in fact became an avid supporter and trustee of the University, serving on the board from 1859 until his death. It seems that the very idea of Toombs’ defiance and wit, more than any substance or recorded history, is what has left a lasting imprint on campus memory.

It’s unclear when the old oak tree first took on its status as an informal memorial, but it wasn’t referenced in the Athens newspapers until July 1886, about seven months after Toombs’ death (and the schlocky, well-timed lightning strike that blasted the tree as Toombs drew his last breath) and nearly 60 years after the famous speech. By this time, any reputation Toombs might have earned as a campus ne’er-do-well would be a faint memory, greatly overshadowed by his career as a general and one of the architects of the Confederacy. Moreover, the campus legend of Toombs probably had renewed significance after the Civil War, given how neatly it fits with the archetype of an incorrigible rebel. After the war, Toombs went on the run to escape Union capture, eventually making his way to Paris. He would return to Georgia in 1867, but refused to accept a pardon from President Johnson, thus disqualifying himself from voting or holding political office. Toombs was the model of the unreconstructed Southerner, but his final years were marked by illness, depression, alcoholism, and the deaths of his son-in-law and beloved wife.

In 1889, the Athens Weekly Banner reported on the Toombs Oak’s loss of a large limb and its general state of decay. The author draws a parallel between the dying tree and the deceased man:

“Both were ushered into prominence at the same moment, both have flourished among their kingdoms with lofty heads—both have fallen at almost simultaneous periods. Neither will soon be forgotten. Time will do its destroying work, will wrinkle fond faces, and whiten golden locks, but in vain will it labor to dim the brilliancy of the name of Toombs or efface the memories that clusters around the venerable oak.”

During Toombs’ “bloom of youth” the tree was itself “fresh and green in its best days,” as the column says. Those days were, of course, the days of the antebellum South—the days of slavery. The columnist is essentially predicting—or perhaps declaring—that the tree site will be one of memorialization long after the tree is gone, and what better memorial to the Lost Cause than a once grand tree that has withered to a shell of its former self?

Time’s “destroying work” has been more effective than predicted. In 2022, the Toombs Oak historical marker was damaged and removed. It has not been replaced and its damage and removal have never been reported in local media. It’s not even clear if the damage resulted from vandalism or something else. Its fate remains uncertain, but it would be surprising for it to make a return at this point. The only other surviving memorial of the oak is the sundial that took its place. The sundial, however, lacks any kind of memorial inscription that links it to Robert Toombs or the oak tree. To most UGA students, faculty, and staff, the sundial is just an attractive feature of north campus. Without the historical marker for context, it seems inevitable that the Toombs Oak will fade further in public memory. And so, in a rather banal way, without protest, petition, or even planning, a Confederate monument exits the scene.